The foundation of every state is the education of its youth.

—Anonymous

Early History of Education

Education is the foundation on which a strong and ever changing society can be built. Great strides have been made impacting generations. Schools have gone through many changes throughout the years, being transformed from a rigid system of memorization and recitation to a more free and individualistic environment. Although the methods and approaches to teaching may differ, a school’s purpose of educating, inspiring growth and uniting community have all stood the test of time. Yet, we do encounter periods of challenge to meet the needs and cultivate the abilities of learners. Today, more so than ever in recent history, we are a crossroads.

A formal school system with many different grades and several schools is a modern invention. Until fairly recently, education was seen as a luxury for the rich and for most people formal education ended in the eighth grade. As a result, many people remained illiterate and poorly educated. The earliest schools of the 19th century were private, religious institutions. Students who could afford these early schools were the children of the rich who were being prepared, from an early age, to become professionals like doctors and lawyers. Courses taught in these schools reflected an elitist attitude with courses including Latin, natural philosophy, and logic. These courses were meant to enlighten young minds and provide a basis for further studies at more prestigious universities.

For most students, this caliber of education was a distant dream. Most students attended school on a limited basis due to the need to work on the family farm. They would learn what would be called the three R’s: reading, writing, and arithmetic. Out of practical necessity, schools were meant to develop basic life skills and a sense of community where neighbor helped neighbor. Since many people were farmers, schools would teach these basic skills to allow children to live successful and productive lives in their farming communities. This form of rudimentary education was, in many ways, perpetuated by the existence of non-professional teachers. A famous Long Islander, by the name of Walt Whitman, once said, about Long Island’s first schools and its teachers: “The teachers of these Long Island country schools are often young poor students from some college or university, who desire to become future ministers, doctors, or lawyers – but,… they take a school, to recuperate and earn a little cash for future efforts.”

These early rural schools also helped foster a sense of unity and community identity. By today’s standards these schools were more democratic. The parents, students and community members retained almost all control of the curriculum and educational experiences of the students. There was little to no state or federal involvement in the instruction and curriculum development of these early community schools. Schools belonged to the community and its inhabitants.

This attitude towards education would change during the latter part of the 19th century with the emergence of the industrial revolution. Suddenly factories began to spread throughout the country and with it came a need for educated workers who could perform simple tasks and obey orders given to them by their superiors. Consequently, the school system focused on traits like obedience, memorization and recitation. The school system taught and reinforced a belief of inferiority, domination and conformity. Each person was a cog in the huge machine called society. This attitude towards education would cement itself into the social fabric. With the advances in both society and educational development, following the industrial revolution, the overall sense of community and civic pride and participation in the education of the community came to a close. As a result, millions of children were turned into obedient and docile adults, who took orders from superiors and didn’t question authority. In more recent times, the ideas and curriculum of schools have begun to change and shift with focus on individual students and their needs.

(Diligent in Study and Respectful in Development – Early Long Island Schooling)

Education & Schools of Early Bellmore

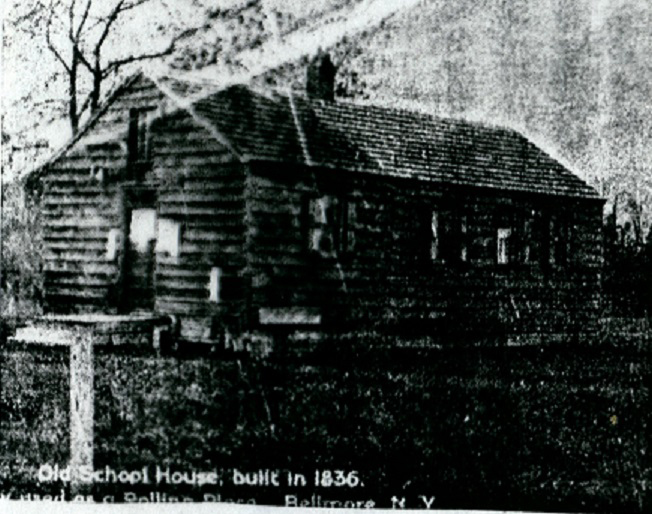

The evolution of education and our schools can be viewed over time through the development and progress of the Bellmore School District. Like many rural towns of the early 19th century, the education and schools of Bellmore were rudimentary by today’s standards. The first school used within the Bellmore community was a converted chicken coop built in 1836. As one could imagine, the conditions inside this one-room building were anything but comfortable. Students would have to chop wood for heat and gather water for use in the building. There was no bathroom and no school lunches. The students usually had to walk between one-five miles a day to attend school.

The typical classroom had two teachers and about fifty students. The eldest students usually sat in the back of the classroom and helped with teaching the younger students. Many of the students did not attend school on a regular basis as they often helped their parents by working on the family farm. For most students, formal education ended in the eighth grade. By the year 1888, the Bellmore community authorized the construction of a two room building located on Orange Street. Around this time the railroad entered town, bringing many professionals and working class people into the rural community of Bellmore.

With the addition of the new professional class, the education system evolved to meet this new demand. Suddenly schools began to cater to the children of new professional parents and changed their curriculum from one based on the agrarian community to one focused on subjects like English, Math, Science and History. Some schools continued to cultivate school gardens which fed students and contributed to experiential learning through the 1950’s. Following the growth of the community and transformation from a rural village to a vibrant community, the school system began to expand as did the student population. By the turn of the century, Bellmore was growing bigger and became the hamlet we know today. At the same time, New York State passed new legislation requiring children between the ages of 8 and 16 to attend a minimum of 130 days of school a year. Instead of being a part-time endeavor for the winter months, or the luxury of the rich, education began to play a more central role in the lives of ordinary people.

(Public Education in the Bellmores)

Bellmore Schools in the 1920s and 1930s

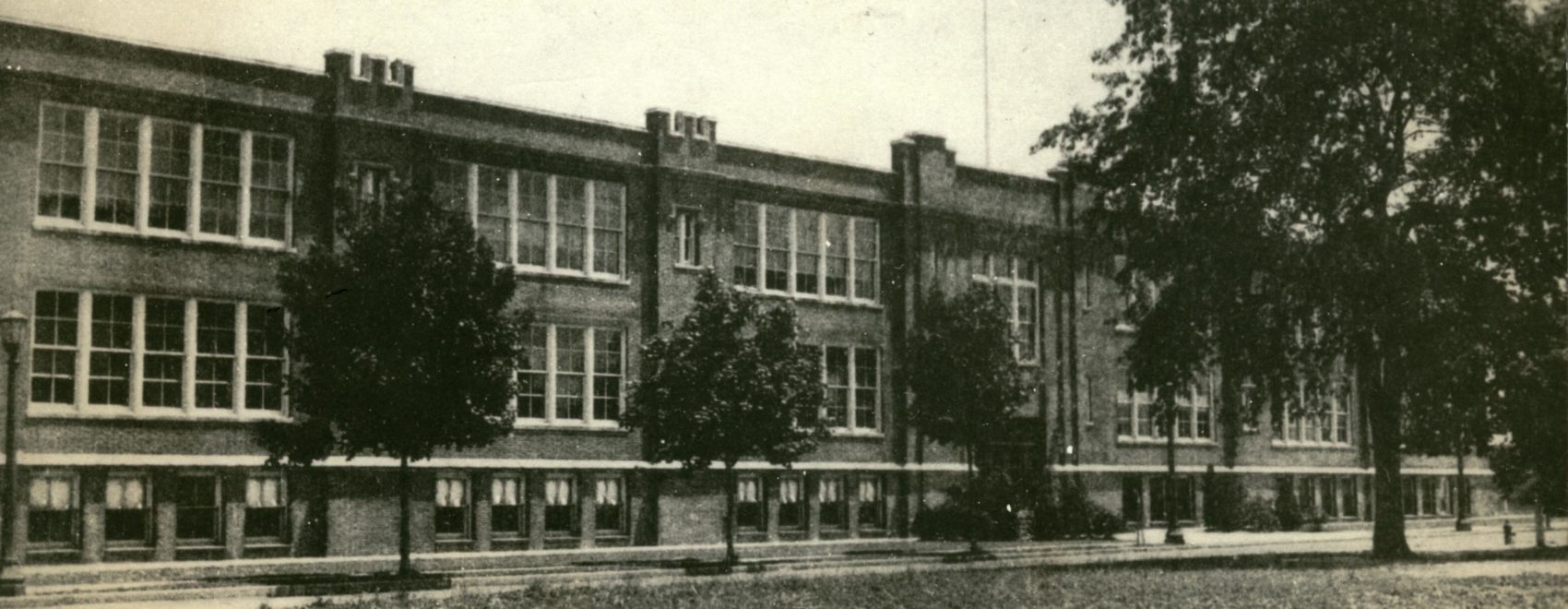

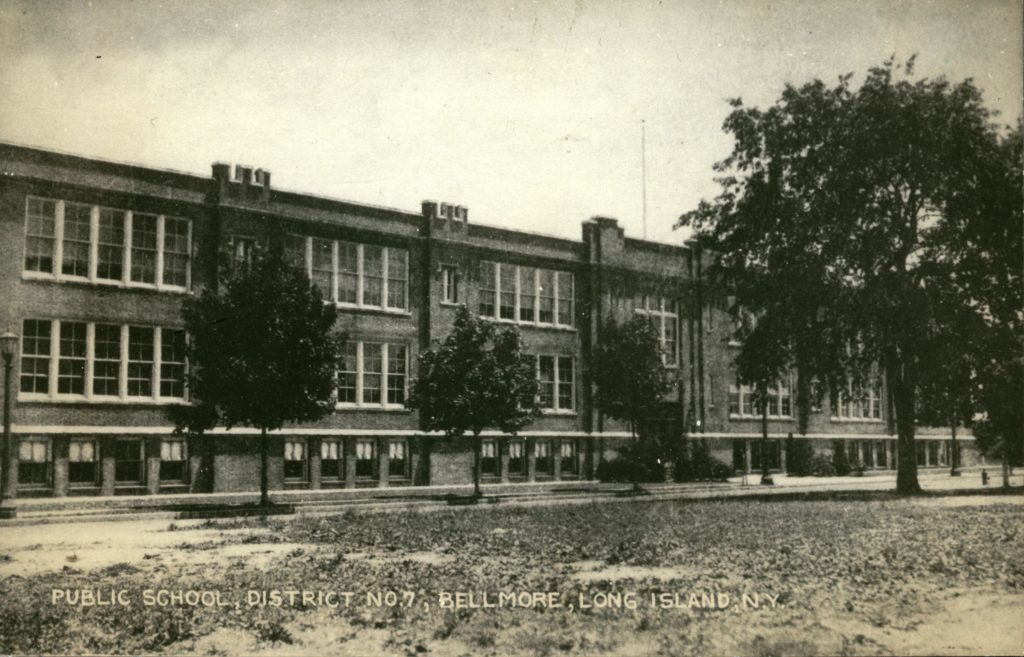

By the 1920’s schools like Newbridge Road Elementary in Bellmore and Camp Avenue School in Merrick were being built. These new schools were huge in comparison to their one-room counterparts. The construction of these schools reflected the growing population of the area as well as the continued evolution of the rural communities of Bellmore and Merrick into the large and vibrant communities of today.

Occurring at the same time as the growth of the school system in Bellmore and Merrick, was the introduction of the automobile to the average family. The development of roads and highway systems led to the diversification and growth of the community into the modern suburbs. The availability of the car opened up these previous rural and small communities to people from New York City who wanted to live close to the city but also own a home and some land. The increased population and diversity of city dwellers helped to spur the demand for quality education as well as the breakdown of the small town mentality and culture of Bellmore and Merrick.

By the 1930’s Bellmore was rapidly expanding into the recognizable town we see today. The school population was growing every year as best exemplified through the growth of employment of teachers from 5 to 26 teachers during this time. The communities of Bellmore and Merrick did not have any high schools and as a result, many parents had to send their children to other high schools in surrounding towns such as Baldwin and Freeport. Now the town faced a crisis. The surrounding high schools couldn’t accept any more residents from Bellmore and Merrick because their schools were being filled with their own residents. Where were the teenagers of Bellmore and Merrick going to go to High School? Each individual town was too small to build their own high school and receive aid from the state government.

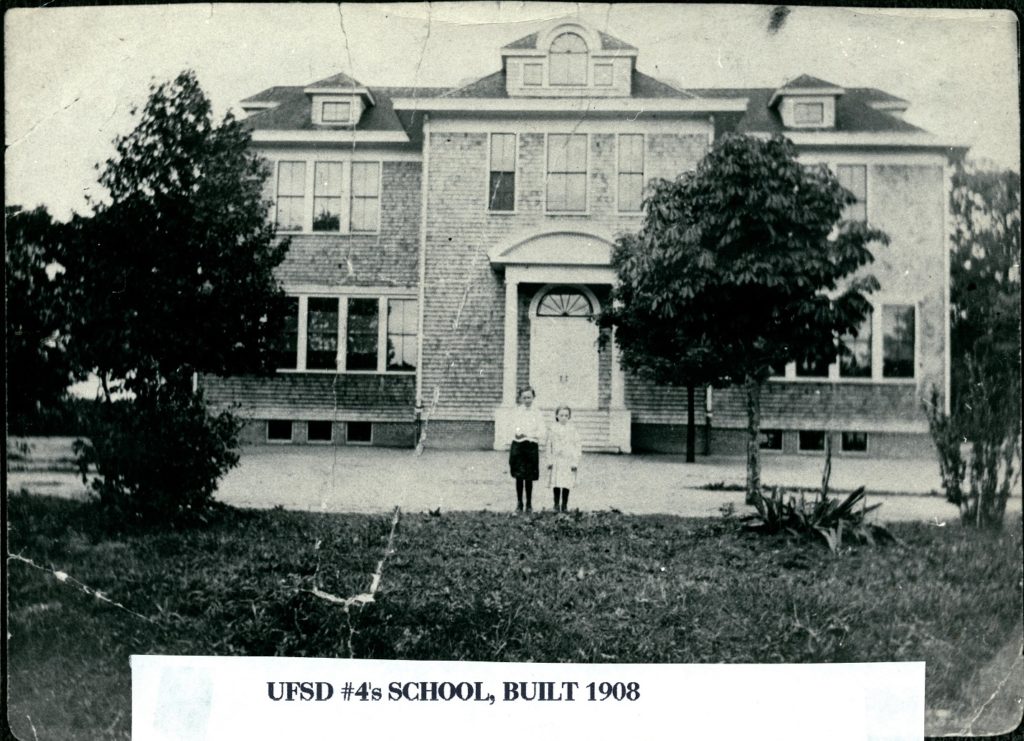

An innovative and creative solution was thought up by Wellington C. Mepham. He proposed the creation of a central high school district that would serve the communities of Bellmore and Merrick. The new high school would be big enough to receive state aid as well as serve as a community center for various events. The creation of the central high school district was the culmination of years of work and community advocacy on behalf of the growing student body. Parents and educators alike banded together to establish this desperately needed school. The new high school, would not only serve the students but be a cultural and community center for this expanding town. The community came together and took pride in the new school and the establishment of the Bellmore-Merrick Central High School District. To deal with the immediate problem facing the community, a temporary high school was established in a six room building from 1908 to 1935 while the new high school was being built. The new high was completed in 1937 and would be named in honor of Wellington C. Mepham for his contribution to the establishment of the Bellmore-Merrick School District.

(Public Education in the Bellmores)

Bellmore-Merrick Schools in the Post-World War II Era

As the towns of Bellmore and Merrick continued to grow, especially during the post-World War II baby boom, the school system would continue to evolve in line with the growing needs of the community. More elementary schools were built in the 1950’s and 1960’s. More high schools and middle schools were also built and existing schools would be renovated to accommodate the large influx of students.

Occurring at the same time as the development of these new schools, American society underwent a cultural shift. The 1960’s and 1970’s shook the cultural bedrock of the nation. Through massive protest movements such as the Civil Rights movement and Anti-War demonstrations the foundations of our society were being redefined and reexamined to fit the changing definition and demographics of the United States. Equality of rights and of opportunity replaced the antiquated ideas of segregation and discrimination. This redefinition of rights and opportunity would spread throughout all of society. The late 1960’s and 1970’s saw the establishment of the Department of Education and the adoption of federal laws designed to ensure the success and inclusion of all students. Laws such as the Elementary & Secondary Education Act (1965) and Individuals with Disability Education Act (1975) were implemented to promote equality and opportunity for all children, no matter their socioeconomic status or cognitive ability.

In many ways these laws were continuing the trend first established during the Progressive Era of the early 1900’s. Both the Progressive Era and the educational reforms enacted in the mid twentieth century tried to focus education on the individual. Through both of these periods of reform, the public education system of the United States underwent transformations in order to better serve the students and community. These laws and reforms enacted in the 60’s and 70’s helped redefine education, make it more accessible, and ensured the maximum opportunity for the success of each student. This period spurred the creation of new methods of teaching focused on enriching students’ knowledge and school experience through interesting and interactive lessons. Instead of monotonous memorization, it was believed that teachers could now focus on knowledge, experiential learning and how to best serve the students’ needs.

(Public Education in the Bellmores)

Education—1980s through 2000s

Recently the more progressive education trends of the 1970’s have begun to wane. The introduction of inclusion classrooms were a critical social justice move and practical step in the right direction. Yet, teacher training to support students with a range of different abilities is still lacking. And, although classification of students with disabilities is needed to provide services within the school setting, labels also perpetuate pigeonholing students with “disabilities” rather than understanding the “whole child” and their abilities.

With the passage of the No Child Left Behind Act in 2001 and the Every Student Succeeds Act of 2015, standardized testing and increased “rigor” have become the bedrock of our children’s education. Measurement of individual student success on standardized tests is used to determine the ratings of our schools. Increased importance of these scores has led to a highly stressful environment for both students, beginning at a very young age, and teachers who attempt to balance curriculum requirements (including new Common Core Standards), teaching to testing mandates and educating students. The belief that test scores are deemed more important than true learning is one that is self-perpetuating despite the good intentions of teachers. Through elementary school, middle school and high school, students have to take these state mandated exams and perform well on them to the detriment of self-esteem and teacher evaluations suffering as a result. Last but not least, NYS limited student diploma options for graduation to a single pathway (Regents) that all students, regardless of ability/disability must pass or qualify for a local diploma “safety-net” (often through an appeal process). Bureaucracy has taken over our schools, especially in regard to learners who need support most. What happened to a sense of community and the drive for knowledge that used to propel students and teachers alike on a never ending quest for knowledge and self-improvement? The modern education system is abandoning the actual needs of its students. Knowledge and the quest to attain knowledge is one of the greatest human journeys and needs to be preserved.

To recapture this sense of purpose and wonder based on a balanced educational agenda, parents, teachers, administrators and politicians need to reassess the importance of state and federal mandates and place renewed importance on the education and well-being of all students. Additionally, we need to resist the charter school movement for corporate profit which is already beginning to hinder public education as we know it. In the meantime, organizations like The Children’s Sangha are working within the community to promote a more holistic, interactive and experiential approach to education which takes the “whole child” into account. The Children’s Sangha works to integrate the function of community and embrace the different abilities of our youth through educational and nature-based programs, services and special events. Students, parents, and teachers can come together as a community “where joy is a way of life, where learning is the highest aim, where love is the ultimate goal”. (Patch Adams)

Education—What’s Next?

As a country we are at a turning point in our education system. Should we focus on test scores and endanger losing our kids to the factory school system rather than develop truly educated citizens who can contribute to society in meaningful ways? A more holistic and integrative approach to our education system where community and a love of learning are stressed above test scores is possible. Our future as a community and as a country are at stake. Children are the future. In order to ensure the best future for every member of society it is imperative that we follow the guidance The Children’s Sangha has to offer. We need to ensure that no student gets left behind and that every student has the opportunity for a quality education, gaining knowledge and experiencing a sense of community as initially intended.

Education and the journey to attain knowledge through one’s community school is rapidly disappearing. Instead of promoting curiosity and thought, our schools and educational system promote bubble sheets and arbitrary tests, increasing anxiety for all. The state is ultimately devaluing the role of teachers, many of whom are striving do what they can to assist students. We are at a time when community activism needs to play a central role and the voices of students, parents and teachers needs to be heard. An important component of 21st century education is developing an awareness of our world and a person’s place in it by inculcating civic engagement in the school curriculum through all grades. Civic engagement is essential in a free and democratic society. It means working to make a difference in the civic life of the community through political and non-political activities.

As society looks to its future we need to remember our past and learn from it. Learning and curiosity should be at the core or our country’s education policy. Knowledge and the gifts attained by having it should be guaranteed to everyone. The promotion of knowledge to all, through civic engagement, individualized approaches to learning and cultivating the different abilities of our youth is critical for student success and the betterment of our society. By ensuring the best education for our youth, we are building the foundation for future prosperity within our communities, states, and nation. Let us remember: “If a child is to keep his inborn sense of wonder, he needs the companionship of at least one adult who can share it, rediscovering with him the joy, excitement and mystery of the world we live in”. (Rachel Carson)