We are on the level with all the rest of God’s creatures. We are not better for being white, than others for being black; and we have no more right to oppress blacks because they are black than they have to oppress us because we are white.”

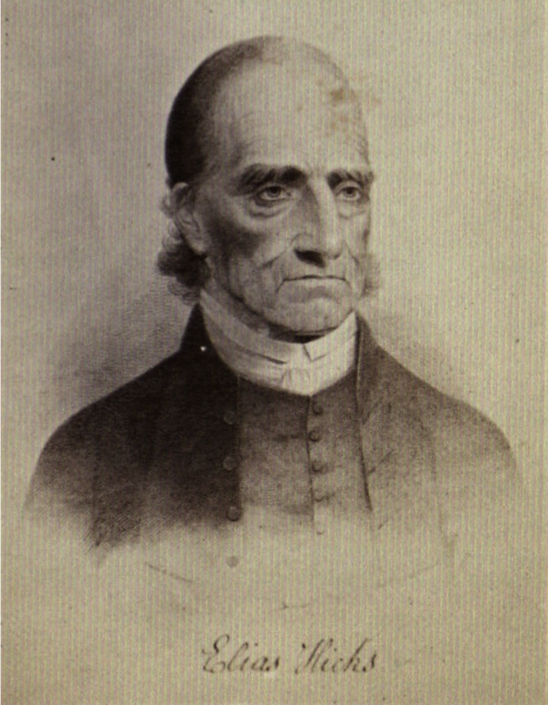

– Elias Hicks (Long Island Quaker)

Introduction

The forced labor and enslavement of Africans in New York state has a long and complicated history. Arriving with the initial Dutch settlement of New Amsterdam in the 17th century, the institution of slavery would become a bedrock of New Amsterdam and then New York life.

Throughout New York State, Africans were forcibly brought to work on farms as well as providing domestic and manufacturing assistance in emerging industries. By the late 17th century, during the time of the American War for Independence, it was estimated that there were “upward of 20,000 slaves in New York.” (Hofstra University, Slavery on Long Island) Despite the pervasiveness of slavery in New York State, many settlers began to question this ingrained institution on moral grounds. One of the most prominent groups to advocate for the abolition of slavery as a social and economic way of life were the Quakers. The Quakers were once a persecuted group in society. The continued persecution and targeting of the Quaker community in Europe led them to migrate to America in search of both political and religious rights. Grounded in a moral belief that every person was born equal before God and motivated by their past experience of persecution, the Quakers became leading advocates for the abolition movement. Eventually, they formed a clandestine network of safe houses and shelters used by runaway slaves to escape to freedom, the Underground Railroad. The contributions of leading Quaker figures such as Elias Hicks and the increasing popular Quaker ideology of equality, helped push New York state to end slavery as well as to inspire the national abolition movement of the 19th century.

Slavery and the African American Experience

Slavery, in the European settlement of New York, brought with it the many dehumanizing and morally repugnant aspects associated with this peculiar institution. Like slavery in the southern United States, the enslaved blacks living in New York had no rights and were victims of continued physical and mental abuse at the hands of their white owners. Strict laws were enacted to ensure the continued social, political, and economic disempowerment of all black residents living in New York. In 1702, a series of laws known collectively as the Black Codes were introduced to regulate and weaken the black population by limiting both their personal rights and the rights of the black community. Some of these laws forbade the congregation of three or more enslaved Africans, outlawed the owning of property by slaves, and held that children born of a slave mother would be slaves. (Hofstra University Slavery on Long Island) These laws as well as other restrictive rules imposed on both slaves and free blacks living in New York solidified the African American community to a position of dependence and powerlessness. Through the passage of these laws white citizens of New York were able to dominate over both the personal and civic lives of all blacks, thus furthering their own power and relegating blacks to an inferior position in society. Even in the face of terrible injustice, many people began to fight against slavery and slowly spark the flame of freedom. There began one of the largest social movements in the nation’s history that would go on to redefine freedom and equality for all. New York passed the Gradual Emancipation Act that freed slave children born after July 4, 1799, but indentured them until they were young adults. In 1817, a new law passed that would free slaves born before 1799 but not until 1827.

Despite the continued persecution and discrimination experienced by the black community living on Long Island, many freedmen and slaves began to speak out and challenge this engrained institution and became active participants in their struggle for liberty. Jupiter Hammon became one of the most famous slaves living in New York who challenged the institution of slavery. Hammon lived on a vast 3,000 acre estate located on Long Island. In his Address to the Negros in the State of New York 1787, he called on white America to live up to its stated ideals of freedom and equality for all men, while also pointing out the struggles and deprivation that slaves faced every day. He wrote, “Liberty is a great thing we may know from our own feelings… I have hoped that God would open their eyes, when they were so much engaged for liberty, to think of the state of the poor blacks, and to pity us.” (Hammon) Hammon’s insistence that white America extend liberty to black slaves and freedmen, reveals the influence slaves such as Hammon worked to exert, despite the daily injustices they faced. Through his powerful writings and speeches, coupled with the organizational power and reach of the Quaker community, Hammon served as an inspiration for all blacks living in bondage as he confronted white society to live up to its ideals.

The Quakers

Quaker Minister Elias Hicks

Historic Malcolm House

A key Quaker figure advocating for the equality of all men and destruction of slavery as an institution was Elias Hicks. Elias Hicks was a prominent Quaker minister and leader of the Quaker community on Long Island in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Through his ministry he advocated for the abolition of slavery throughout Long Island and stressed the personal responsibility the Quaker community had for the education of slaves and newly freed men. Elias Hicks’s belief that all men are created equal and are entitled to the same basic human rights is illustrated in his statement from the annual Quaker public pronouncement, “We are however full of the mind that Negros as rational creatures are born free, and where the way opens liberty ought to be extended to them.” (Velsor, 24) Elias Hicks pronouncement for the freedom and rights of black Americans had important and long-lasting ramifications not only within the Quaker community on Long Island, but also within the emerging abolition movement. Through Hick’s understanding of universal rights, the Quaker community began to free their slaves and provide them with jobs and an education. Additionally, Hick’s recognition of blacks as “rational and free”, challenged dominant perceptions of white superiority and thus forced society to reconcile with the enslavement of their fellow human beings. Ultimately Hicks propelled the Quaker community on a path to becoming the most ardent defenders of black rights while helping to redefine the black community’s status.

A newfound collective effort by the Quakers to free slaves and provide the basic ingredients needed to preserve and promote liberty was demonstrated by the Quakers’ buying of slaves solely to free them. This is evident in Velsor’s book where she wrote, “ William Loines sets my Negro man Lige free whom I purchased for the purpose of freeing him.” (25) The action of buying a man to emancipate him from the bonds of slavery exhibits the power that Hicks’ message of equality had on the Quaker community. Moreover Elias Hicks called on Quakers to provide an education to the newly freedmen by setting up schools, evident by the statement, “[Elias Hicks] was the driving force behind the formation of the charity society… the charity society’s mission was to help improve the lives of the poor among the African people by educating their children.” (Veslor 44) The Quakers establishment of charity schools throughout Long Island helped provide the tools necessary to enable lasting freedom and greater equality for the black community. The skills learned enabled slaves to work towards freedom with newfound knowledge and provided freedmen with more options for success in life.

The Underground Railroad

The creation of the charity schools paved the way for more people in the Quaker community of Long Island to participate in the Underground Railroad. Two sites associated with the Quaker community and alleged to be part of the Underground Railroad was the Jackson-Malcolm House and the Maine Maid Inn located in what is now referred to as the Jericho Historic Preserve. According to local folklore, the Jackson-Malcolm House “had a secret attic school where escaping slaves were taught reading, writing and other subjects to blend in better with freed men and women and thus escape detection from slave captors.” (Jacobsen, Waiting for Daylight) Although the evidence linking the Jackson-Malcolm house to the Underground Railroad is unsubstantiated, this location’s connection to both the Quaker community coupled with the community’s efforts to educate and empower Black Americans through education, illustrates the plausibility of this site serving as a secret school for escaping slaves. An additional site believed to be connected with the Underground Railroad was the Maine Maid Inn. It is alleged that “fugitive slaves found temporary refuge through a second-floor cupboard door at the Maine Maid Inn.” (Jacobsen ,Waiting for Daylight) Local folklore pertaining to both of these sites communicates the power and influence the Quaker community had on the abolition movement while working with the large black community located in Jericho and neighboring towns. Countless people’s lives were transformed and the foundation of the institution of slavery slowly crumbled and was replaced with a new understanding of equality and dignity for all men.

Quaker Legacy

Although the Quaker presence on Long Island has faded, their message of equality and the empowerment of all individuals through education and civic engagement lives on through various community organizations such as The Children’s Sangha. Through community programs and partnerships, The Children’s Sangha works to continue the legacy established by the Quakers and movements of times past, to foster the development of a more equitable and just society no matter a person’s race, gender, types of abilities, or any other trait. The Children’s Sangha believes every person has unique strengths that should be cultivated and celebrated, fostering mutual respect. Furthermore, through grassroots efforts, The Children’s Sangha encourages all people to become civically engaged to promote such principals. Like the Quaker community before them, The Children’s Sangha strives to encourage our youth within the community to become leaders, emulating the spirit of Elias Hicks through advocacy and action.

And, to do so, the establishment of Sangha Education Center at Malcolm House is underway! Even though the issues we face may be different from our Quaker counterparts of the past, their ideals of equity, respect, and civic responsibility are just as important today. By participating with The Children’s Sangha, everyone can contribute to the education and well-being of all towards the betterment of society, in alignment with timeless Quaker ideals.